Nov. 4, 2007

Houston Chronicle

THE IMMIGRATION DEBATE

Fence's presence felt - Residents on both sides of one border crossing say barrier is doing what it was intended to do

By Dudley Althaus

PALOMAS, MEXICO — At this fabled border crossing, where the last armed conflict between the United States and Mexico flared, the rancorous debate over the new U.S. anti-immigrant fence has been resolved.

The fence works, residents north and south of it say. At least it works for now on this snippet of the line.

"You hear it all the time: Fences don't work. Fences don't work," said Mark Winder, a transplanted New Englander and part-time deputy sheriff who lives on a small ranch outside Columbus, N.M., where a 3-mile stretch of wall was completed in August. "I live 2½ miles from the border, and the fence is working."

Many merchants agree in Palomas, once a sleepy farm town, now a booming haven for smugglers.

"The fence has destroyed the economy here," said Fabiola Cuellar, a hardware-store clerk on the main street of Palomas who used to sell supplies to the throngs heading north from here. "Things are going back to the way they were before."

Of course, with only about one-fifth of the fence complete, migrants from Mexico and other countries who had planned to cross the border illegally in places such as Palomas-Columbus can simply go elsewhere.

But U.S. officials have vowed to complete nearly 400 miles of the fence by the end of next year. Workers in August and September built 70 miles of it here, in Arizona and in parts of California. Thousands more Border Patrol agents, electronic monitors and other measures will tighten the squeeze.

James Johnson's 3,000-acre family farm abuts the border west of Columbus. "Where there is a will, there's a way," said Johnson, 32, of some migrants' ability to get around, over or under any barrier.

"But anything is better than just running across the border anytime you want to," he said.

Satisfaction, shrugs

Whether good fences make good neighbors is another, perhaps more crucial, debate entirely. This new wall has sparked political controversies in the U.S., and stoked a "been-here, done-this" rancor among many Mexicans. But here, where the rampart is now part of the landscape, it tends to elicit satisfied nods from Americans and resigned shrugs from Mexicans.

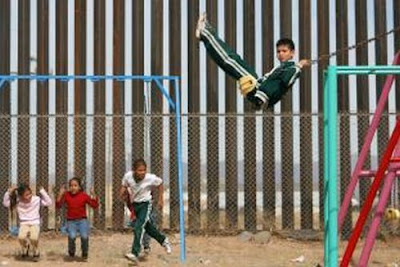

"It's their territory. They can do what they want with it," said Armando Villasana, 50, the principal of a Palomas elementary school whose hardpan recess yard smacks into the new bulwark. "On the border we're accustomed to changes."

The fence, a 15-foot-high phalanx of girders tightly spaced and rooted deeply in the earth, is a jarring obstruction to the otherwise "for miles and miles" view of these parched high plains.

Rather than a solid wall, the barrier more closely resembles a vertical iron grate. It lets people on either side see across the border while preventing them from crossing it.

Its builders say the fence permits wildlife free passage. But the spaces between the posts seem tight enough to prevent even the wiliest coyote from slipping through.

The Border Patrol made about 36,000 apprehensions in New Mexico in the first 10 months of fiscal 2007, which ended Sept. 30. That's a huge drop from fiscal 2006, when nearly 74,000 illegal crossers were caught on the state's border, according to government records.

Palomas and Columbus, dusty pinpricks in the vast Chihuahuan Desert, were carved into border history nine decades ago when Pancho Villa, the Mexican revolutionary and bandit, raided the New Mexican town with about 450 troops.

The attack, repulsed by a detachment of U.S. cavalry, left 18 Americans and as many as 100 Mexican raiders dead. And it sparked the nearly yearlong expedition of 10,000 U.S. soldiers led by Gen. John. J. Pershing deep into Mexico in fruitless pursuit of Villa.

In the nine decades since, the two villages settled into an easygoing and shared obscurity. Like much of the border from El Paso to San Diego, the line here was marked by the sort of fence that might separate one field from another in farm country anywhere.

By day, by night

Families tend to have members on both sides of the border. U.S. farms like the Johnsons' relied on Mexican workers hopping the border to work by day and heading back south at night.

Migrants heading farther north would often stop by the border farms to ask for water or food for the journey. They were never turned away, Johnson said, and they would often do chores to repay the kindness.

That changed in the 1990s when tighter border enforcement — first to the east in El Paso, then to the west in Arizona — funneled the growing waves of migrants from the Mexican interior and Central America though Columbus and other parts of New Mexico.

Vehicles carrying illegal narcotics or illegal migrants would plow through the border fence across the Johnsons' land. Scores of migrants led by smugglers, called coyotes, would trek through the fields, scaring livestock and leaving trash. The smugglers would sometimes be armed.

"I understand the plight of the people," said Johnson, who speaks Spanish and whose family has been farming here since 1918. "I live with these people. If I were in their shoes, I'd be doing the same thing.

"What I don't like is the business that transporting them across the border has become," he said. "Things became dangerous."

Complaints from the Johnsons and others on the border prompted New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson to demand federal action.

A waist-high reinforced barrier designed to stop vehicles was built on the border — a stretch of it on the Johnson farm stood a few feet inside Mexico. National Guard troops camped near Columbus.

Richardson called on Mexico to bulldoze houses in Las Chepas, a largely abandoned hamlet just across the border from the Johnson's farm that has served as a staging area for smugglers.

"From a law enforcement perspective, it's curtailed a lot of our problems," said Sharon Mitamura, a deputy sheriff who patrols the border on either side of Columbus.

"You have legitimate people who are coming here," she said of the border jumpers.

"But you also have the coyotes who are bringing people across," she said, "and you have the bandidos who are stealing."

The same human crush that alarmed the Johnsons created an industry in Palomas.

Restaurants and stores sprouted. Small hotels and boarding houses went up. Buses and other vehicles transported people.

But with the good came a share of the bad.

'People are affected'

The newcomers were as much strangers here as they were in New Mexico. Crime increased. They left trash in their wake, kept people awake at night because their crossings set dogs barking. Locals who had often been able to slip north for a day of shopping or visiting family now found it harder because of the increased Border Patrol presence.

"There are families here who have family members over there, so people are affected," said Villasana, the school principal, as he watched girls play a pick-up game of soccer in the shadow of the fence. "But the fence is felt more (by people) in the interior than here."

Then Villasana told of a daydreaming young student who gazed out the window at the new wall during class last month.

Villasana asked the boy, What are you thinking about?

"They have built us a wall of shame, professor," the student answered.

'How is that?" Villasana asked.

"It's shame because people have to leave our country to find work," the boy responded.

Now it's boring

At the small museum in Columbus dedicated to Pancho Villa's raid and its aftermath, Lee Robinson regales tourists with lurid accounts of the bravery of the U.S. soldiers who repelled the Mexican attackers.

A recent transplant from Erie, Pa., Robinson is a Minuteman, one of the volunteers who flocked to the border several years ago determined to stop illegal immigration. After a stint in Arizona, Robinson followed the migrant flow east to Columbus. Now, he's contending with getting what he wished for.

"That fence, I love it," Robinson said one recent afternoon after finishing a detailed explanation of the raid for a father and son visiting from Ohio.

But Robinson quickly added that "being a Minuteman in New Mexico is getting pretty boring."

"There's no illegals here to be found," he said, wistfully.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Fences DO Make (Tolerably) Good Neighbors

Posted by

No Apology

at

7:02 AM

![]()

Subscribe to:

Comment Feed (RSS)

|